Written by Scott P. Roberts

My earliest memory of Florida is waking up to the view out a window of the Holiday Beach motel on Seaway Drive in Ft. Pierce. A gleaming white ship was passing just outside, moving quickly and quietly. As it glided out of sight my focus jumped to its white foam wake spreading out on deep blue, undulating waters. I moved closer to the window and found the river’s opposite bank, not far away, and traced it to a cut in the land that quickly bent out of sight. I looked farther left and saw that the land was really a group of islands, sometimes connected, that gave way to a broad river with a mainland beyond.

My eyes darted back right, past the cut, over scrub brush and palm trees, to huge rocks with a beach behind them. Small waves were breaking on the beach this August morning, forty-two years ago. I looked farther right and learned that the deep blue river just outside my window opened out to the sea a few hundred yards ahead. The ship was out there now, quickly becoming a white dot on an enormous blue canvas.

My eyes danced back and forth, taking in the ocean, the beach, the islands and the vast open waterway. This place—the Indian River Lagoon, her inlet at Ft. Pierce, and her north and south jetty beaches—instantly became home. My fondest boyhood memories are of surfing and diving at those beaches, and boating, skiing and swimming with all manner of life in the clear, warm, grassy waters of the Indian River Lagoon.

Even as a teenager I realized that the life of the Lagoon had everything to do with those grasses. Gliding over and through them I could see that the Lagoon’s creatures and many ocean fish and shellfish were born and raised there. I watched the manatees eat them. I swam through them and up to the many islands and mangroves with dolphins and schools of fish and, of course, game fish. Much calmer than when I encountered them on the reef near north jetty, the redfish, sea trout, snook, snapper and drum moved slowly just above the grass, or hung almost motionless in the sand and grass shallows by the islands, sometimes with dorsal fins in open air. I learned later that the Indian River Lagoon is the most biologically diverse estuary in North America. Her grasses and brackish water are the foundation of life for 4,300 species of plants and animals, and one of America’s most diverse populations of birds.

II

My most recent memory of Florida is waking up to another view of the Indian River Lagoon. In 1979 my fiancée and I left for graduate school in New York, promising to be right back. But school, kids and work turned “right back” into decades. When we finally had the chance to come home we jumped at it, though we landed on the west coast of Florida instead of the east.

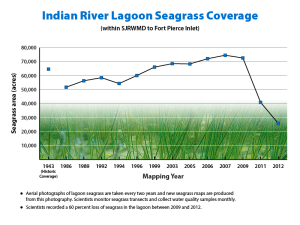

Not long after our return, through some mysterious transaction, I received a copy of an email about the despoliation of my boyhood home. As I dug for more information I came upon a flood of articles and reports, almost too much to take in, and much too much to bear. I steadied myself and remembered to keep my eye on the Lagoon’s seagrasses. Sure enough, they offered a good outline of her story since I left[i]:

There was a strong effort through the 1980s and 1990s to keep the Indian River Lagoon healthy. Nothing could be done about the Army Corps of Engineers releasing billions of gallons of polluted freshwater into the Lagoon whenever Lake Okeechobee rose above 15.5 feet.[ii] But in the IRL watershed the Florida Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) enforced strict limits where they could, and encouraged limits where they could not, on the “total daily maximum load” (TDML) of nitrogen and phosphorous that entering the Lagoon.

Why nitrogen and phosphorous? Found in fertilizers (and, thereby, in industry and wastewater treatment plant discharges, the runoff from farms and residential areas, and in those Lake Okeechobee waters), nitrogen and phosphorous are essential food for algae. When the water is warm and the weather is calm, an abundance of nitrogen and phosphorus can cause an explosion of alga growth. Over a vast body of water like the Indian River Lagoon this rapid growth looks like the emergence of enormous blooms—algae blooms. As the blooms steal the sunlight the Lagoon’s seagrasses die. Then as the alga die, fungi and bacteria in the decay process deplete the oxygen in the water, leading to fish kills. So, keeping the TDML low does a lot to keep the IRL seagrasses and other plants, and animals, healthy.

Then also, from the late 1990s up to about 2010, according to St. Johns River Water Management District scientist Joel Steward, nature helped the IRL in two big ways. First, Florida had a period of low rainfall[iii] so there simply was less runoff into the Lagoon.

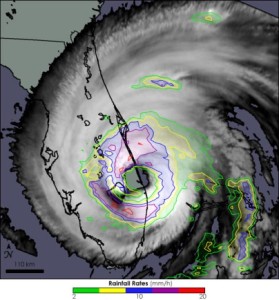

Second, in 2004, hurricanes Jeanne and Frances hit the Lagoon and stirred up a lot of the nutrients in her bed. Pushed up into the water column, these nutrients were then flushed away as Atlantic storm surges blasted in through the inlets and just as quickly sucked back out. Even though I was away by 2004, I remember coming back that year to help my parents remove debris. I also remember looking out at a refreshed Indian River Lagoon.

Second, in 2004, hurricanes Jeanne and Frances hit the Lagoon and stirred up a lot of the nutrients in her bed. Pushed up into the water column, these nutrients were then flushed away as Atlantic storm surges blasted in through the inlets and just as quickly sucked back out. Even though I was away by 2004, I remember coming back that year to help my parents remove debris. I also remember looking out at a refreshed Indian River Lagoon.

So from the late 1990s through the early 2000s, the amount of algae in the Lagoon decreased, the water became clearer, and the seagrass beds? They grew, thickened and extended their reach, covering parts of the Indian River Lagoon that had been bare since before WWII.

Then according to Mr. Steward, with studies showing the Lagoon cleaner and enjoying near-record growth of its seagrasses, the “DEP came up with a basin action management plan that [said] counties, cities and water districts do not need to do anything else to reduce nutrient loads because conditions in the lagoon are improving.” Steward continues:

“The good mood lasted up until 2011 when the now infamous superbloom of oxygen-consuming algae exploded in the northern lagoon, killing 44 percent of the seagrass in eight months and ushering in a period of rapid decline in lagoon health that continues today.”[iv]

It’s clear that relaxing standards helped bring about the superbloom explosion. Then too, nature played its role. As Mr. Steward reported at the 2013 Indian River Lagoon Symposium at  Harbor Branch Oceanographic Institute:

Harbor Branch Oceanographic Institute:

“…two exceptionally cold winters, hypersalinity caused by a drought, and the mysterious die-off of drift algae set the stage for the ecological disaster. A pulse of nutrients, including fertilizer runoff, that washed into the lagoon during two March downpours helped trigger the collapse.”[v]

It is 2013 now and there’s no sign of the seagrass coming back. Instead there are more algae blooms and mysterious deaths of manatees, dolphins and pelicans. And in my boyhood home stretch of the IRL there are toxic algae blooms.

It is 2013 now and there’s no sign of the seagrass coming back. Instead there are more algae blooms and mysterious deaths of manatees, dolphins and pelicans. And in my boyhood home stretch of the IRL there are toxic algae blooms.

Based on tests by the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission, the Florida Department of Health is urging residents to avoid contact with these algae in the entire estuary from the St. Lucie Canal to the St. Lucie Inlet. What are the rules when toxic blooms hit?

Do not cook with, eat, or drink from these waters (boiling will not remove toxins).

Do not swim or shower in these waters.

Do not allow your pets to swim in, drink from, or play near these waters.

Do not water ski or ride a personal watercraft over algae mats.

Do not water your lawns or gardens with these waters.[vi]

The timing of this latest toxic bloom is very close to another enormous, polluted freshwater release by the Army Corps of Engineers:

“Normally found only in freshwater, green goo is invading the St Lucie River and salt water estuary, due to Lake Okeechobee freshwater releases. The river, already struggling from the billions of gallons of dirty water being poured in, just met its nemesis.”[vii]

III

“To live at the expense of the source of life is obviously suicidal. Though we have no choice but to live at the expense of other life, it is necessary to recognize the limits and dangers involved: past a certain point in a unified system, “other life” is our own.” –Wendell Berry

I am deeply fond of my Indian River Lagoon memories because they’re set in one of the most beautiful natural environments I have ever encountered. But what jumps out at me now is their youthful innocence. I don’t recall a moment’s thought about nitrogen and phosphorus loads. I don’t remember thinking about pollution at all, or about the Lagoon seagrasses having needs. I certainly didn’t understand the IRL to be a delicately balanced system, one that accommodates so many species because its water is brackish, and because of “…its unique geographical location, which straddles the transition zone between colder temperate and warmer sub-tropical biological provinces.”[viii]

Tropical storms and hurricanes seemed always to leave the Lagoon refreshed, not defeated or depleted. I do remember a few hot summer, low tide, smelly-seaweed-on-her-shore days. But on those days we were all a little smelly, and out past shore her waters were clear, her grasses thick, and her fish jumping. I didn’t think about the health of the Indian River Lagoon, and I certainly didn’t think that I had anything to do with it. I was a dot on her canvas, like that gleaming white ship in my earliest memory of Florida, playing in all her life-giving immensity.

Forty-two years after making these memories, swaths of the Lagoon are choking on algae. Some of the alga is toxic; all of it is killing her grasses, plants and animals. Where the alga is toxic nothing can healthily swim or eat. We wonder why dolphins and pelicans starve to death in or near this alga, and manatees die with bellies full of it. Half of the Indian River Lagoon’s life-giving grasses are gone.

Yes, nature has had a big say in what’s happened to the Lagoon. But to stop at that thought is to stop exactly where I did in the thoughts of my youth. There was surely a moment when humans could justifiably believe that we had no effect on the health of the Lagoon or the wider Earth—that we could do whatever we wished to ecosystems and subsystems, without consequence. But that moment is as long gone on the timescale of humankind as the moments that created my boyhood memories are on mine.

And this is the message of what’s happening in the Indian River Lagoon. The Lagoon is nature on a grand scale, and her death or near death is clearly, incontrovertibly, a result of how we value and use her: as a backdrop for our homes and farms and their runoff, a paradise for thousands upon thousands of anglers each year, a dump site for our polluted freshwater lakes and rivers, and a highway for our big ships and playground for our little ones. She is stating, without room for ambiguity and in the national and the international press, that the human way of life is folly, that we are and have been for many years, “living at the expense of the source of life,” including our own life. Wake up, wake up.

But if what’s happening in the Indian River Lagoon is clear evidence that our actions have a tremendous, negative impact on the health of the Earth and its subsystems, what keeps us from jettisoning the rest of the idea that we can use the Earth and its subsystems in any way we wish? What keeps us from letting go is, again, that this is no mere idea, but the foundation of our very way of life. Our interactions with the rest of nature assume it, our culture—our customs and traditions, ethics (only humans have intrinsic worth) and religions (humans have dominion over the earth and all its creatures)—promotes and defends it, and our economy—our livelihood—rests upon it.

Put in another way, humankind cannot move to the new foundational idea that we must only use the Earth and its subsystems in ways that benefit or at least healthily sustain them, until it reimagines its relationship to nature, its culture (including its ethics and religions), and perhaps most importantly, until it creates a great many jobs that sustain rather than exploit our source of life. It’s a very tall order to accomplish all this. And it’s the only way to go. And that’s why Ecology Florida provides this website, this forum for people heading or thinking about heading in this direction. Come help the new foundation cure, and help stand new culture and new work firmly upon it. Come speak your piece now, come work. Thank you.

The effort to change our way of life before our life’s source is expended will take several generations, if we have them. So whether she lives or dies, remember the Indian River Lagoon, her grasses, and the beautiful, diverse life they sustained. Remember to your children and grandchildren that she was a sunrise not a sunset, that as she lay dying she woke all the people on Earth.

[i] Graph from the Saint Johns River Water Management District, http://www.sjrwmd.com/itsyourlagoon/

[ii] St. Augustine Record, 9/19/2012, Army Corps of Engineers drains Lake Okeechobee

[iii] VeroNews.com, 2/28/2013, Lagoon in mid-2000s aided by natural phenomena

[iv] VeroNews.com, Ibid

[v] VeroNews.com, 8/1/2013, Perfect storm caused lagoon superbloom.

[vi] CBS12.com, 7/19/2013, Toxic green and black goo coating the Indian River Lagoon

[vii] CBS12.com, Ibid

[viii] Smithsonian Marine Station at Fort Pierce, http://www.sms.si.edu

[box title=”Author Info” color=”#e0f8d3″]Scott P. Roberts is an adjunct ethics professor, gardener and writer living in Odessa, Florida. Earlier in life he was a researcher in ethics and computing at Carnegie Mellon University and director of Annenberg Media (now Annenberg Learner) in Washington, D.C. [/box]

Leave a Reply